Programming Your App's Memory

Just as people need to remember things, so do apps. This chapter examines how you can program an app to remember information.

When someone tells you the phone number of a pizza place for a one-time immediate call, your brain stores it in a memory slot. If someone calls out some numbers for you to add, you also

store the immediate results in a memory slot. In such cases, you are not fully conscious of how your brain stores information or recalls it.

An app has a memory as well, but its inner workings are far less mysterious than those of your brain. In this chapter, you'll learn how to set up an app's memory, how to store information

in it, and how to retrieve that information at a later time.

Named Memory Slots

An app's memory consists of a set of named memory slots. Some of these memory slots are created when you drag a component into your app; these slots are called properties. You

can also define named memory slots that are not associated with a particular component; these are called variables. Whereas properties are typically associated with what is visible in an

app, variables can be thought of as the app's hidden "scratch" memory. 242 Chapter 16: Programming Your App's Memory

Properties

Components-at least the visible ones like Button, TextBox, and Canvas-are part of the user interface. But to the app, each component is completely defined by a set of properties. The

values stored in the memory slots of each property determine how the component appears.

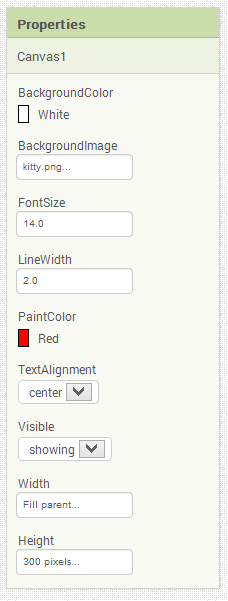

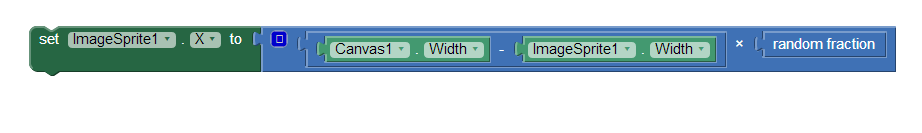

You can modify property memory slots directly in the Component Designer, as shown in Figure 16-1.

The Canvas component of Figure 16-1 has six properties. The BackgroundColor and PaintColor are memory slots that hold a color. The BackgroundImage holds a

filename (kitty.png). The Visible property holds a Boolean value (true or false, depending on whether the box is checked). The Width and Height slots

hold a number or a special designation (e.g., "Fill parent").

When you change a property in the Component Designer, you are specifying how the app should appear when it's launched. Someone using the app (the end user) never sees that there is a

memory slot named Height containing a value of 300. The end user only sees the user interface with a component that is 300 pixels tall.

Figure 16-1. Modifying the memory slots in the property form to change the app's appearance

Defining Variables

Like properties, variables are named memory slots, but they are not associated with a particular component. You define a variable when your app needs to remember something that is not being stored

within a component property. For example, a game app might need to remember what level the user has reached. If the level number were going to appear in a Label component, you might not

need a variable, because you could just store the level in the Text property of the Label component. But if the level number is not something the user will see, you'd define a

variable to store it.

The Presidents Quiz (Chapter 8) is another example of an app that needs a variable. In that app, only one question of the quiz should appear at a time in the user interface, while the rest of

the questions are kept hidden from the user. Thus, you need to define a variable to store the list of questions.

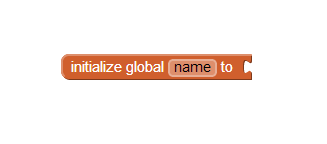

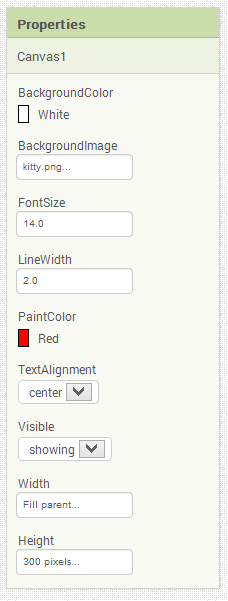

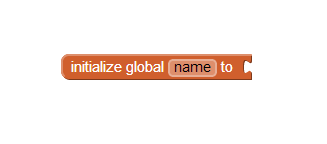

Whereas properties are created automatically when you drag a component into the Component Designer, you define a new variable explicitly in the Blocks Editor by dragging out a global

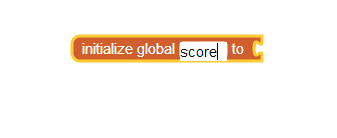

variable block. You can name the variable by clicking the text "variable" within the block, and you can specify an initial value by dragging out a number, text,

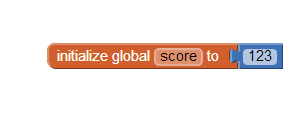

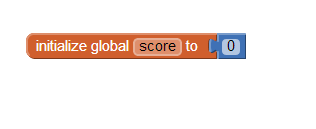

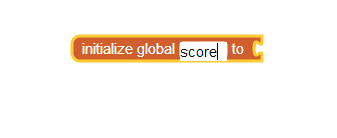

color, or make a list block and plugging it in. Here are the steps you'd follow to create a variable called score with an initial value of 0:

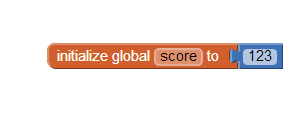

- Drag the def variable block (Figure 16-2) from the Definitions folder in the Built-In blocks.

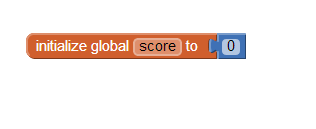

- Change the name of the variable by clicking on the text "variable" and typing "score", as illustrated in Figure 16-3.

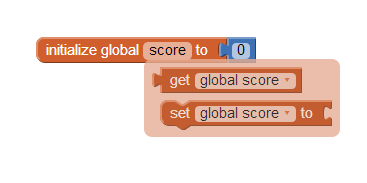

- Set the initial value to a number by dragging out the number block and plugging it into the variable definition (Figure 16-4)

- Change the initial value from the default number (123) to 0 (Figure 16-5)

When you define a variable, you tell the app to set up a named memory slot for storing a value. These slots, as with properties, are not visible to the user.

The initialization block you plug in specifies the value that should be placed in the slot when the app begins. Besides initializing with numbers or text, you can also place a make

a list block into the global variable block. This tells the app that the variable names a list of memory slots instead of a single value. To learn more about lists, see Chapter 19.

Setting and Getting a Variable

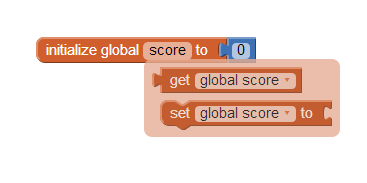

When you define a variable, App Inventor creates two blocks for it, a set and a get. You can access these blocks by hovering over the variable name in the initialization block as

shown in Figure 16-6.

Figure 16-6. The initialization block contains set and get blocks for that variable

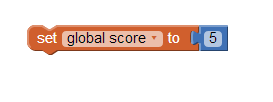

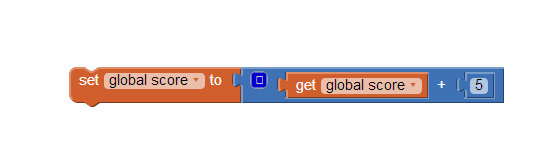

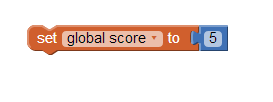

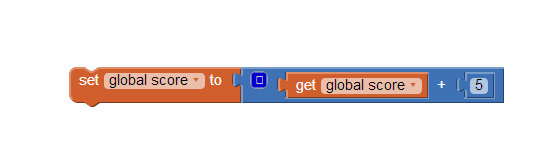

The set global to block lets you modify (set) the value stored in the variable. For instance, the blocks in Figure 16-7 place a 5 in the variable score. The term

"global" in the set global score to block refers to the fact that the variable can be used in all of the program's event handlers and procedures(globally). The newest version of

App Inventor allows you to also define variables that are "local" to a particular procedure or event handler (this is not covered here).

Figure 16-7. Placing a number 5 into the variable score

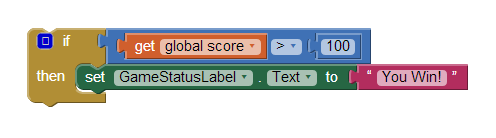

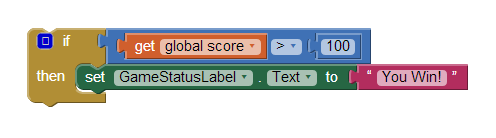

The block labeled get global score helps you retrieve the value of a variable. For instance, if you wanted to check if the score was 100 or greater, you'd plug the get

global score block into an if test, as demonstrated in Figure 16-8.

Figure 16-8. Using the global score block to get the value stored in the variable

Setting a Variable to an Expression

You can put simple values like 5 into a variable, but often you'll set the variable to a more complex expression (expression is the computer science term for a formula). For example, when

the user clicks Next to get to the next question in a quiz app, you'll need to set the currentQuestion variable to one more than its current value. When someone does something bad

in a game app, you might modify the score variable to 10 less than its current value. In a game like MoleMash (Chapter 3), you change the horizontal (x) location of the

mole to a random position within a canvas. You'll build such expressions with a set of blocks that plug into a set global to block.

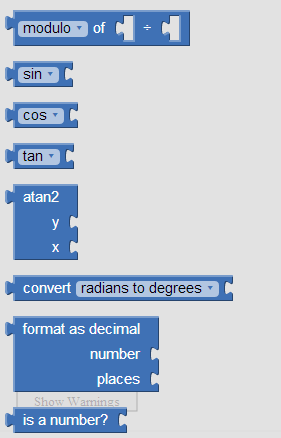

Incrementing a Variable

Perhaps the most common expression is for incrementing a variable, or setting a variable based on its own current value. For instance, in a game, when the player scores a point, the

variable score can be incremented by 1. Figure 16-9 shows the blocks to implement this behavior.

Figure 16-9. Incrementing the variable score by 1

If you can understand these kinds of blocks, you're well on your way to becoming a programmer. You read these blocks as "set the score to one more than it already is," which is another way to say

increment your variable. The way it works is that the blocks are interpreted inside out, not left to right. So the innermost blocks-the global score and the number

1 block-are evaluated first. Then the + block is performed and the result is "set" into the variable score.

Supposing there were a 5 in the memory slot for score before these blocks, the app would perform the following steps:

- Retrieve the 5 from score's memory slot.

- Add 1 to it to get 6.

- Place the 6 into score's memory slot (replacing the 5).

For more on incrementing, see Chapter 19.

Building Complex Expressions

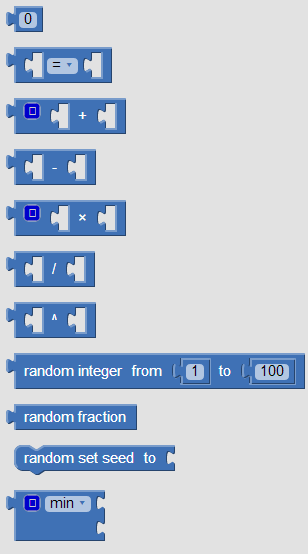

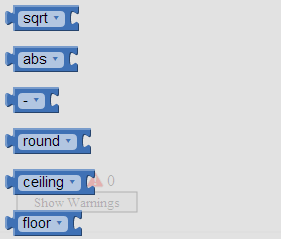

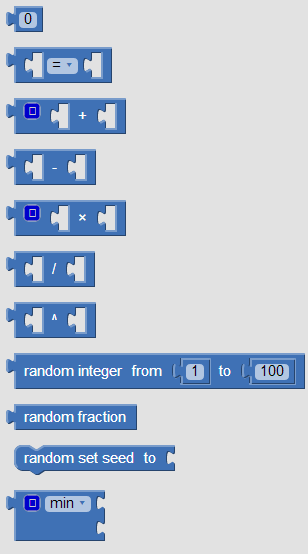

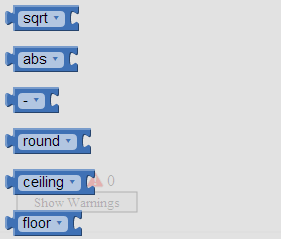

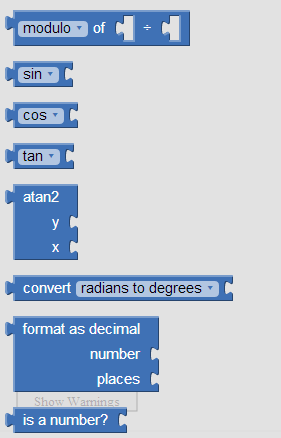

In the Math drawer (Figure 16-10), App Inventor provides a wide range of mathematical functions similar to those you'd find in a spreadsheet or calculator.

Figure 16-10. The blocks contained in the Math drawer

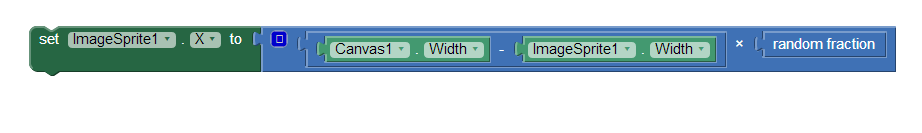

You can use these blocks to build a complex expression and then plug them in as the righthand-side expression of a set global to block. For example, to move an image

sprite to a random column within the bounds of a canvas, you'd configure an expression consisting of a * (multiply) block, a – (subtract) block, a Canvas.Width property, and a random

fraction function, as illustrated in Figure 16-11.

Figure 16-11. You can use math blocks to build complex expressions like this one

As with the increment example in the previous section, the blocks are interpreted by the app in an inside-out fashion. Supposing the Canvas has a Width of 300 and the ImageSprite

has a Width of 50, the app would perform the following steps:

- Retrieve the 300 and the 50 from the memory slots for Canvas1.Width and ImageSprite.Width, respectively.

- Subtract: 300 – 50 = 250.

- Call the random fraction function to get a number between 0 and 1 (say, .5).

- Multiply: 250 * .5 = 125.

- Place the 125 into the memory slot for the ImageSprite1.X property.

Displaying Variables

When you modify a component property, as in the preceding example, the user interface is directly affected. This is not true for variables; changing a variable has no direct effect on the app's

appearance. If you just incremented a variable score but didn't modify the user interface in some other way, the user would never know there was a change. It's like the proverbial tree falling in

the forest: if nobody was there to hear it, did it really happen?

Sometimes you do not want to immediately manifest a change to the user interface when a variable changes. For instance, in a game you might track statistics (e.g., missed shots) that will only

appear when the game ends.

This is one of the advantages of storing data in a variable as opposed to a component property: it allows you to show just the data you want when you want to show it. It also allows you to

separate the computational part of your app from the user interface, making it easier to change that user interface later.

For example, with a game you could store the score directly in a Label or in a variable. If you store it in a Label, you'd increment the Label's Text property when points were

scored, and the user would see the change directly. If you stored the score in a variable and incremented the variable when points were scored, you'd need to include blocks to also move the value

of the variable into a label.

However, if you decided to change the app to display the score in a different manner, the variable solution would be easier to change. You wouldn't need to find all the places that change the

score; those blocks would be unmodified. You'd only need to modify the display blocks.

The solution using the Label and no variable would be harder to change, as you'd need to replace all the increment changes with, say, modifications to the Width of the label.

Summary

When an app is launched, it begins executing its operations and responding to events that occur. When responding to events, the app sometimes needs to remember things. For a game, this might be

each player's score or the direction in which an object is moving.

Your app remembers things within component properties, but when you need additional memory slots not associated with a component, you can define variables. You can store values into a variable

and retrieve the current value, just like you do with properties.

As with property values, variable values are not visible to the end user. If you want the end user to see the information stored in a variable, you add blocks that display that information in a label

or another user interface component.