HelloPurr, MoleMash, and the other apps covered in this book's early chapters are relatively small software projects and don't really require what people often refer to as engineering. That term is coopted from other industries; think about building a scale model of a house from a premade kit versus designing and building your own real home. That's a slightly exaggerated example, but in general, the process of building something extremely complex that requires a significant amount of forethought, planning, and technique falls under the umbrella of engineering. As soon as you take on a more complicated project, you'll realize that the difficulty of building software increases rapidly for each bit of complexity you add-it is not anywhere close to a linear relationship. For most of us, it takes a few hard knocks before we realize this fact. At that point, you'll be ready to learn some software engineering principles and debugging techniques. If you're already at that point, or if you're one of those few people who want to learn a few techniques in the hope of avoiding some of those growing pains, this chapter is for you.

Here are some basic principles that we'll cover in this chapter:

If you follow this advice, you will save yourself time and frustration and build better software. But you probably won't follow it every time! Some of this advice may seem counterintuitive. Your natural inclination is to think of an idea, assume you know what your users want, and then start piecing together blocks until you think you've finished the app. Let's go back to the first principle and look at how to understand what your users want before you start building anything.

In the movie Field of Dreams, the character Ray hears a voice whisper, "If you build it, [they] will come." Ray listens to the whisper, builds a baseball field in the middle of his Iowa corn patch, and indeed, the 1919 White Sox and thousands of fans show up.

You should know right now that the whisperer's advice does not apply to software. In fact, it's the opposite of what you should do. The history of software is littered with great solutions for which there is no problem ("Let's write an app that will tell people how long it takes to drive their car to the moon!"). Solving a real problem is what makes for an amazing (and hopefully, in most cases, profitable) app. And to know what the problem is, you've got to talk to the people who have it. This is often referred to as user-centered design, and it will help you build better apps.

If you meet some programmers, ask them what percentage of the programs they have written have actually been deployed with real users. You'll be surprised at how low the percentage is, even for great programmers. Most software projects run into so many issues that they don't even see the light of day.

User-centered design means thinking and talking to prospective users early and often. This should really start even before you decide what to build. Most successful software was built to solve a particular person's pain point, and then-and only then-generalized into the next big thing.

Build a Quick Prototype and Show It to Your Prospective Users Most prospective users won't react too well if you ask them to read a document that specifies what the app will do and give their feedback based on that. What does work is to show them an interactive model for the app you're going to create-a prototype. A prototype is an incomplete, unrefined version of the app. When you build it, don't worry about details or completeness or having a beautiful graphical interface; build it so that it does just enough to illustrate the core value-add of the app. Then, show it to your prospective users, be quiet, and listen.

Incremental Development When you begin your first significantly sized app, your natural inclination might be to add all of the components and blocks you'll need in one grand effort and then download the app to your phone to see if it works. Take, for instance, a quiz app. Without guidance, most beginning programmers will add blocks with a long list of the questions and answers, blocks to handle the quiz navigation, blocks to handle checking the user's answer, and blocks for every detail of the app's logic, all before testing to see if any of it works. In software engineering, this is called the Big Bang approach.

Just about every beginning programmer uses this approach. In my classes at USF, I will often ask a student, "How's it going?" as he's working on an app.

"I think I'm done," he'll reply.

"Splendid. Can I see it?"

"Ummm, not yet; I don't have my phone with me."

"So you haven't run the app at all?" I ask.

"No.…"

I'll look over his shoulder at an amazing, colorful configuration of 30 or so blocks. But he hasn't tested a single piece of functionality.

It's easy to get mesmerized and drawn into building your UI and creating all the behavior you need in the Blocks Editor. A beautiful arrangement of perfectly interconnected blocks becomes the programmer's focus instead of a complete, tested app that someone else can use. It sounds like a shampoo commercial, but the best advice I can give my students-and aspiring programmers everywhere-is this:

&tbsp;Code a little, test a little, repeat.

Build your app one piece at a time, testing as you go. Soon enough, even this process will become surprisingly satisfying, because you'll see results sooner (and have fewer big, nasty bugs) when you follow it.

There are two parts to programming: understanding the logic of the app, and then translating that logic into some form of programming language. Before you tackle the translation, spend some time on the logic. Specify what should happen both for the user and internally in the app. Nail down the logic of each event handler before moving on to translating that logic into blocks.

Entire books have been written on various program design methodologies. Some people use diagrams like flowcharts or structure charts for design, while others prefer handwritten text and sketches. Some believe that all "design" should end up directly alongside your code as annotation (comments), not in a separate document. The key for beginning programmers is to understand that there is a logic to all programs that has nothing to do with a particular programming language. Simultaneously tackling both that logic and its translation into a language, no matter how intuitive the language, can be overwhelming. So, throughout the process, get away from the computer and think about your app, make sure you're clear on what you want it to do, and document what you come up with in some way. Then be sure and hook that "design documentation" to your app so others can benefit from it. We'll cover this next.

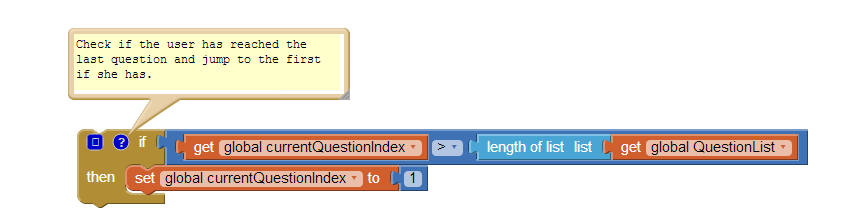

If you've completed a few of the tutorials in this book, you've probably seen the small yellow boxes within the blocks (see Figure 15-1). These are called comments. In App Inventor, you can add comments to any block by right-clicking it and choosing Add Comment. Comments are just annotation; they don't affect the app's execution at all.

Figure 15-1. Using a comment on the if block to describe what it does in plain English

Why comment then? Well, if your app is successful, it will live a long life. Even after spending only a week away from your app, you will forget what you were thinking at the time and not have a clue what some of the blocks do. For this reason, even if nobody else will ever see your blocks, you should add comments to them.

And if your app is successful, it will undoubtedly pass through many hands. People will want to understand it, customize it, extend it. As soon as you have the wonderful experience of starting a project with someone's uncommented code, you'll understand completely why comments are essential.

Commenting a program is not intuitive, and I've never met a beginning programmer who thought it was important. But I've also never met an experienced programmer who didn't do it.

Problems become overwhelming when they're too big. The key is to break a problem down. There are two main ways to do this. The one we're most familiar with is to break a problem down into parts (A, B, C) and tackle each one individually. second, less common way is to break a problem into layers from simple to complex. Add a few blocks for some simple behavior, test the software to make sure it behaves as you want, add another layer of complexity, and so on.

Let's use the MakeQuiz app in Chapter 10 as an example for evaluating these two methods. That app lets the user navigate through the questions by clicking a Next button. It also checks the user's answers to see if she's correct. So, in designing this app, you might break it into two parts-question navigation and answer checking and program each separately.

But within each of those two parts, you could also break down the process from simple to complex. So, for question navigation, start by creating the code to display only the first question in the list of questions, and test it to make sure it works. Then build the code for getting to the next question, but ignore the issue of what happens when you get to the last question. Once you've tested that the quiz will take you to the end, add the blocks to handle the "special case" of the user reaching the last question.

It's not an either/or case of whether you should break a problem down into parts or into layers of complexity, but it's worth considering which approach might help you more based on what you're actually building.

When an app is in action, it is only partially visible. The end user of an app sees only its outward face-the images and data that are displayed in the user interface. The inner workings of software are hidden to the outside world, just like the internal mechanisms of the human brain (thankfully!). As an app executes, we don't see the instructions (blocks), we don't see the program counter that tracks which instruction is currently being executed, and we don't see the software's internal memory cells (its variables and properties). In the end, this is how we want it: the end user should see only what the program explicitly displays. But while you are developing and testing software, you want to see everything that is happening.

You as the programmer see the code during development, but only a static view of it. Thus, you must imagine the software in action: events occurring, the program counter moving to and executing the next block, the values in the memory cells changing, and so on.

Programming requires a shift between two different views. You begin with the static model-the code blocks-and try to envision how the program will actually behave. When you are ready, you shift to testing mode: playing the role of the end user and testing the software to see if it behaves as you expect. If it does not, you must shift back to the static view, tweak your model, and test again. Through this back and forth process, you move toward an acceptable solution.

When you begin programming, you have only a partial model of how a computer program works-the entire process seems almost magical. You begin with some simple apps: clicking a button causes a cat to meow! You then move on to more complex apps, step through some tutorials, and maybe make a few changes to customize them. The beginner partially understands the inner workings of the apps but certainly does not feel in control of the process. The beginner will often say, "it's not working," or "it's not doing what it's supposed to do." The key is to learn how things work to the point that you think more subjectively about the program and instead say things such as, "My program is doing this," and "My logic is causing the program to.…"

One way to learn how programs work is to trace the execution of some simple app, representing on paper exactly what happens inside the device when each block is performed. Envision the user triggering some event handler and then step through and show the effect of each block: how the variables and properties in the app change, how the components in the user interface change. Like a "close reading" in a literature class, this step-by-step tracing forces you to examine the elements of the language-in this case, App Inventor blocks.

The complexity of the sample you trace is almost immaterial; the key is that you slow down your thought process and examine the cause and effect of each block. You'll gradually begin to understand that the rules governing the whole process are not as overwhelming as you originally thought.

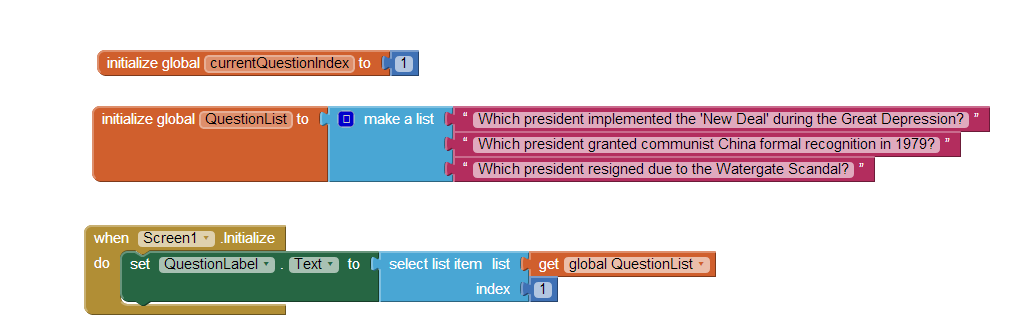

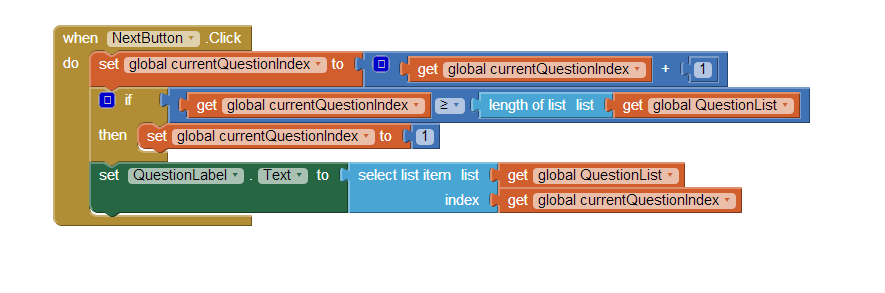

For example, consider these blocks, shown in Figures 15-2, which are slight alterations of those from the Presidents Quiz app (Chapter 8).

Figure 15-2. Setting the Text in QuestionLabel to the first item in QuestionList when the app begins

Do you understand this code? Can you trace it and show exactly what happens in each step?

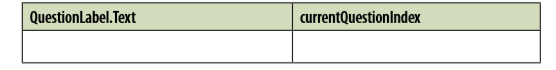

You start tracing by first drawing memory cell boxes for all pertinent variables and properties. In this case, you need boxes for the currentQuestionIndex and the QuestionLabel.Text, as shown in Table 15-1.

Table 15-1. Boxes to hold the changing text and index values

Next, think about what happens when an app begins-not from a user's perspective, but internally within the app when it initializes. If you've completed some of the tutorials, you probably know this, but perhaps you haven't thought about it in mechanical terms. When an app begins:

Tracing a program helps you understand these mechanics. So what should go in the boxes after the initialization phase?

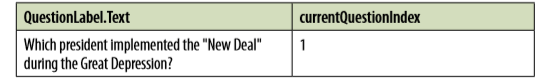

As shown in Table 15-2, the 1 is in currentQuestionIndex because the variable definition is executed when the app begins, and it initializes it to 1. The first question is in QuestionLabel.Text because Screen.Initialize selects the first item from QuestionList and puts it there.

Table 15-2. The values after the Presidents Quiz app initializes QuestionLabel.Text currentQuestionIndex

Next, trace what happens when the user clicks the Next button.

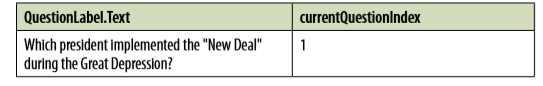

Figure 15-3. This block is executed when the user clicks the NextButton

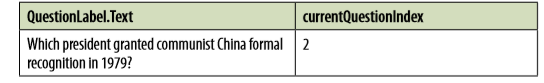

Examine each block one by one. First, the currentQuestionIndex is incremented. At an even more detailed level, the current value of the variable (1) is added to 1, and the result (2) is placed in currentQuestionIndex. The if statement is false because the value of currentQuestionIndex (2) is less than the length of QuestionList (3). So the second item is selected and put into QuestionLabel.Text, as illustrated in Table 15-3.

Table 15-3. The values after NextButton is clicked

Trace what happens on the second click. Now currentQuestionIndex is incremented and becomes 3. What happens with the if? Before reading ahead, examine it very closely and see if you can trace it correctly.

On the if test, the value of currentQuestionIndex (3) is indeed greater than or equal to the length of QuestionList. So the currentQuestionIndex is set to 1 and the first question is placed into the label, as shown in Table 15-4.

Table 15-4. The values after NextButton is clicked a second time

Our trace has uncovered a bug: the last question in the list never appears!

It is through discoveries like this that you become a programmer, an engineer. You begin to understand the mechanics of the programming language, absorbing sentences and words in the code instead of vaguely grasping paragraphs. Yes, the programming language is complex, but each "word" has a definite and straight-forward interpretation by the machine. If you understand how each block maps to some variable or property changing, you can figure out how to write or fix your app. You realize that you are in complete control.

Now if you tell your friends, "I'm learning how to let a user click a Next button to get to the next question; it's really tough," they'd think you were crazy. But such programming is very difficult, not because the concepts are so complex, but because you have to slow down your brain to figure out how it, or a computer, processes each and every step, including those things your brain does subconsciously.

Tracing an app step by step is one way to understand programming; it's also a timetested method of debugging an app when it has problems.

Tools like App Inventor (which are often referred to as interactive development environments, or IDEs) provide the high-tech version of pen-and-paper tracing through debugging tools that automate some of the process. Such tools improve the app development process by providing an illuminated view of an app in action. These tools allow the programmer to:

NOTE: Watching, a feature of AI1, is not yet implemented in AI2.

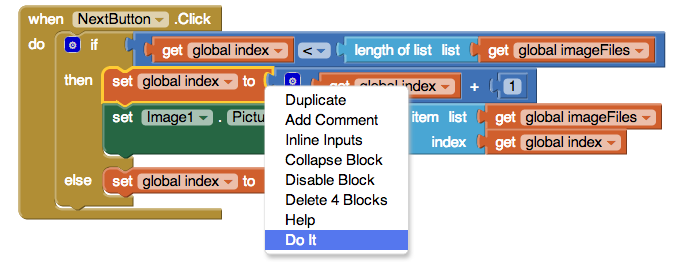

While the Watch mechanism allows you to examine variables during an app's execution, another tool called Do It lets you try out individual blocks outside the ordinary execution sequence. Right-click any block and choose Do It, and the block will be performed. If the block is an expression that returns a value, App Inventor will show that value in a box above the block.

Do It is very useful in debugging logic problems in your blocks. Consider the quiz's NextButton.Click event handler again, and suppose it has a logic problem in which you don't navigate through all the questions. You could test the program by clicking Next in the user interface and checking to see if the appropriate question appears each time. You might even watch the currentQuestionIndex to see how each click changes it.

But this type of testing only allows you to examine the effect of entire event handlers. The app will perform all the blocks in the event handler for the button click before allowing you to examine your watch variables or the user interface.

The Do It tool lets you slow down the testing process and examine the state of the app after any block. The general scheme is to initiate user interface events until you get to the problem point in the app. After discovering that the third question wasn't appearing in the quiz app, you might click the NextButton once to get to the second question. Then, instead of clicking the NextButton again and having the entire event handler performed in one swoop, you could use Do It to perform the blocks within the NextButton.Click event handler one at a time. You'd start by right-clicking the top row of blocks (the increment of currentQuestionIndex) and choosing Do It, as illustrated in Figure 15-7.

This would change the index to 3. App execution would then stop-Do It causes only the chosen block and any subordinate blocks to be performed. This allows you, the tester, to examine the watched variables and the user interface. When you're ready, you can choose the next row of blocks (the if test) and select Do It so that it's performed. At every step of the way, you can see the effect of each block.

Figure 15-7. Using the Do It tool to perform the blocks one at a time

It ‘s important to note that performing individual blocks is not just for debugging. It can also be used during development to test blocks as you go. For instance, if you were creating a long formula to compute the distance in miles between two GPS coordinates, you might test the formula at each step to verify that the blocks make sense.

Another way to help you debug and test your app incrementally is to activate and deactivate blocks. This allows you to leave problematic or untested blocks in an app but tell the system to ignore them temporarily as the app runs. You can then test the activated blocks and get them to work fully without worrying about the problematic ones. You can deactivate any block by right-clicking it and choosing Deactivate. The block will be grayed out, and when you run the app it will be ignored. When you're ready, you can activate the block by right-clicking it again and choosing Activate.

The great thing about App Inventor is how easy it is-its visual nature gets you started building an app right away, and you don't have to worry about a lot of low-level details. But the reality is that App Inventor can't figure out what your app should do for you, much less exactly how to do it. Even though it's tempting to just jump right into the Designer and Blocks Editor and start building an app, it's important to spend some time thinking about and planning in detail what exactly your app will do. It sounds a bit painful, but if you listen to your users, prototype, test, and trace the logic of your app, you'll be building better apps in no time.